Introduction

The Perceived Value Product Model is a method of defining a product in terms of the value that is perceived by the customer or end user.

And this examination of the perceived value philosophy yields the identification of the leading experts in business management who have all worked to refine or advance this concept. This research project also confirms that the winners in any industry or economic sector are the organizations that come closer to seeing the world as their customers do.

Three leading authorities in business have contributed the majority of the perceived value strategy: Philip Kotler, Ted Levitt, and Regis McKenna. All three of these authors have used the same foundational arguments.

The Foundation of the Perceived Value Model

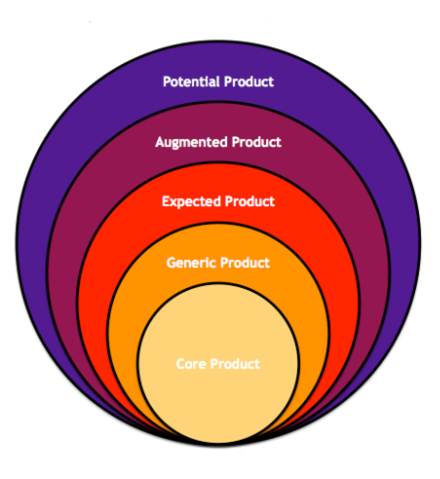

Philip Kotler’s Five Product Levels Model was introduced in 1967 through his book “Marketing Management.” This model was developed specifically to help salespeople understand the customer’s perspective.

The Five Product Levels Model outlines a hierarchy of product features, starting with the core product and progressing through expected features, augmented features, and potential future enhancements, allowing sales teams to understand how to add value to their products to meet customer expectations.

All of Kotler’s five levels are developed to support and advance product features and functions according to customers’ needs and preferences. The intended outcomes are to increase customer satisfaction, save money, increase sales, and improve customer retention.

The Second Generation of Perceived Value

In his book entitled “The Marketing Imagination” (published in 1983) Ted Levitt, a professor at Harvard Business School drew attention to the fact that consumers purchase more than the core product itself. Rather, they purchase the core product combined with complimentary attributes, the majority of which are intangible.

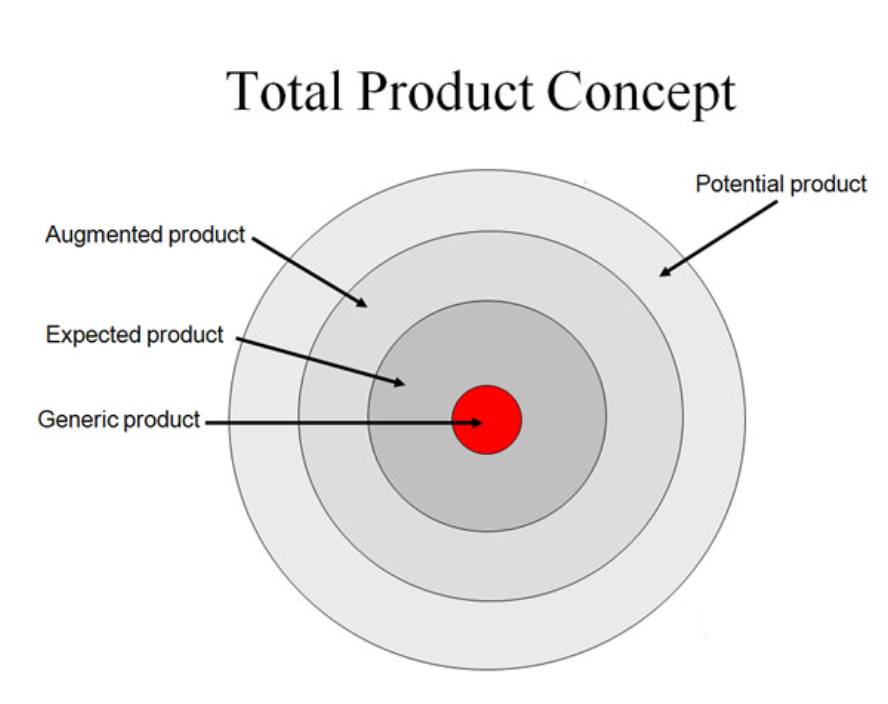

The “total product concept” was Levitt’s vision of how intangible elements could be added to a physical product, transforming it into an offering that was often more valuable than the physical attributes alone. Levitt’s description of the total product is composed of four elements:

Generic Product: The basic functionality or core benefit of the product.

Expected Product: What customers typically expect to receive when buying a product, including standard features and quality.

Augmented Product: Additional features and services that differentiate the product from competitors, adding extra value for the customer.

Potential Product: Possible future enhancements or innovations that could further improve the product and address evolving customer needs.

Tom Peters refined Levitt’s total product concept by proposing an extension that describes the differences between insider and customer perceptions in three different types of industries – technology, service and retail. Peters called his adaptation of the total product concept: “In the Eye of the Beholder.”

The Third Generation of Perceived Value

Following the theories developed by Philip Kotler and Ted Levitt, a Silicon Valley consultant named Regis McKenna, revised this concept yet again and called it the “whole product.”

Proposed in 1989, McKenna defined the whole product as a generic or core product, augmented by everything that is needed for the customer to have an urgent reason to buy.

Missing Elements and the Fourth Generation

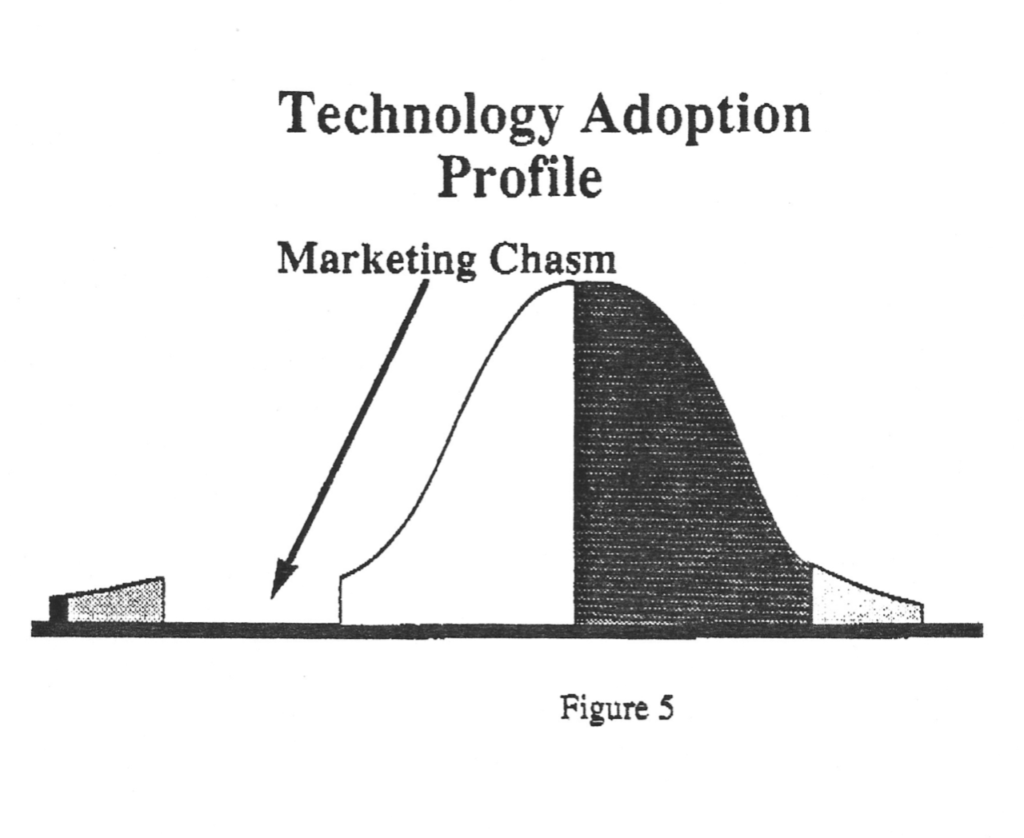

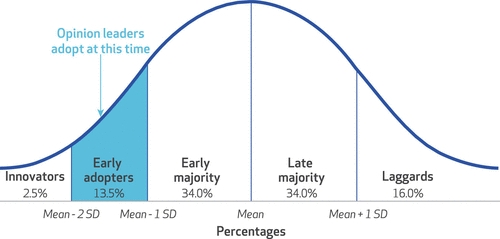

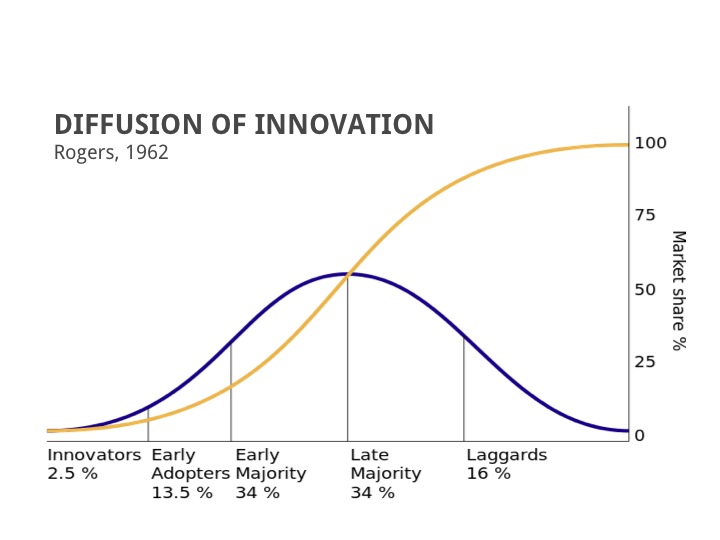

Kotler, Levitt, Peters and McKenna all seem to imply that the additions made to a physical product are equally attractive to all types of customers. In all three models, there is no discussion of, or reference to, the innovation-adoption lifecycle, called Diffusion of Innovations.

The possible outcome is the belief that all customers are the same, especially in terms of how they evaluate products and services. Whereas we know that even people who want to accomplish the same task, have different reasons for doing so and those reasons are constantly changing.

To correct this missing element, the latest iteration of the value perception concept emphasizes “dynamic perception” which incorporates the way products or ideas move through the innovation-adoption lifecycle. And dynamic perception has now become a critical element in the analysis of how customers perceive value. This unexamined dimension of product evolution over time is the primary thinking behind an updated model called The Low Risk Recipe™.

In this fourth iteration of perceived value, not all intangible attributes are developed at the same time. Rather than the uniform or constant perception that is implied in previous models, The Low Risk Recipe emphasizes developing intangibles unevenly over time. The pace and depth of intangibles development then determines the rate of innovation adoption.

As products move through the adoption process, intangibles must be added to the core innovation so that the product meets the safety needs of each adopter group in sequence. Often, pioneering new products lose their initial prominence because a new entrant is more successful in assembling a product based on a more effective mix of intangibles. This can be the case even if the second product is not technically superior.