Introduction

If you’ve ever built an innovative, or novel product, chances are that you’ve thought about the adoption of innovations before.

Will anyone use my new innovation? How can I get more people to use it? And why do people initially show substantial interest, but then leave?

To answer these questions, we need to understand how and why people adopt new ideas, products, or methods.

The purpose of this article is to summarize the most relevant and helpful theories that explain the adoption of innovations. And we begin with the foundational model called Diffusion of Innovations.

This diffusion theory provides long-term guidance for sustained business success, and also illustrate the root cause of why over 90% of all new products fail.

Key Takeaways

Here are the most important concepts to remember:

- The word innovation (and its cousin, “disruptive”) are two of the most widely misunderstood and misused terms in the English language.

- Innovation is an idea, practice, or object perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption. An innovation can come from anywhere.

- The most critical distinction when comparing types of innovation is: anything that forces new learning or behavior change is called a discontinuous innovation. Anything that is a refinement of something that is already in widespread use is called a continuous innovation.

- According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the words disruptive and discontinuous meant the same thing until a book called “The innovators Dilemma” re-purposed the word disruptive. Ever since then, there has been massive confusion.

- Most people want an innovation to enhance, not overthrow, the established ways of doing business.

- A person can be an early adopter of a one innovation and a late adopter of another innovation. Past adoption behavior means nothing when predicting future behavior.

- The management skill-sets required to commercialize a discontinuous innovation are completely opposite of those needed to commercialize a continuous innovation.

- A company can grow to be substantial size just by serving innovators and early adopters with a discontinuous innovation.

- An innovation can come from any source: a person, a government agency, a declining enterprise, a startup, a high school science class, a non-profit, etc.

- A company that only has experience selling continuous innovations and mainstream products, will struggle badly when trying to go-to-market with a discontinuous innovation.

- All successful mainstream innovations share three elements in common. These three elements act to reduce the perception of risk associated with the adoption of innovations.

Adoption of Innovations Overview

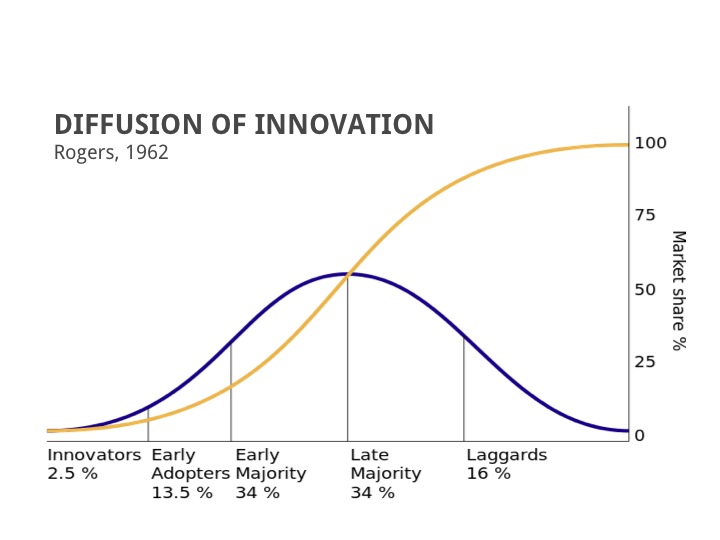

Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) is a theory popularized by Ohio State University professor Everett Rogers, that explains how, why, and the rate at which an innovation spreads through a population or social system. It is the starting point for understanding the adoption of innovations.

Published in 1962, the book Diffusion of Innovations offers three valuable insights into the process of innovation adoption:

- What qualities make an innovation spread successfully.

- The importance of peer-to-peer networks.

- Understanding the needs of each adoption segment.

These insights have been tested in more than 6000 research studies and field tests, so this is probably the most reliable model in the field of behavioral change.

Definitions

An innovation is an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption.

However, there is a critical distinction when defining types of innovation: anything that forces new learning or behavior change is called a “discontinuous innovation.” Anything that is a refinement of something that is already in widespread use is called a “continuous innovation.”

The most common mistake made by people across the globe is to associate innovation with radical change.

Adoption is an individual process detailing the series of stages one undergoes from first hearing about a product to finally adopting it.

Diffusion, however, signifies a group process, which suggests how an innovation spreads among individual end users.

Overall, the diffusion process essentially encompasses the adoption process of several individuals over time. In other words, adoption is an individual or organizational process that leads to diffusion as a systemic or cultural process.

Disruption Not Required

Innovation is the adoption of new ideas, practices or objects. But leapfrogging is not commonly observed across most innovations that are adopted by organizations. The process is one of gradual improvement.

The vast majority of all people and organizations want to buy a productivity improvement for existing operations. They are looking to minimize the disruption of their current methods. And they want evolution, not revolution.

Why Does a Common Definition of Innovation Matter?

Too many authors, analysts and self-appointed experts blur the distinction between the creation of innovations and the adoption of innovations. Remember, it is one thing to create something new, but it has no value if no one uses it.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the words disruptive and discontinuous had exactly the same definition until a book called “The innovators Dilemma” re-purposed the word disruptive. Ever since then, there has been massive confusion.

Many of the mistakes made in describing the adoption of innovations are based in the belief that innovation requires a quantum leap forward. When in fact, the most credible research studies have found that disruption is not necessary and in the majority of cases disruption is not present.

Innovation is the adoption of new ideas, practices or objects. But innovation that provides a quantum leap in capability (called leapfrogging) is not commonly observed across most organizations. The process is one of gradual improvement and disruption is not necessary.

In a recent study by the Brookings Institute, researchers found that innovation is often [mistakenly] related to “leapfrogging” using new technologies. However, in reality, technological progress is more often a continuous and accumulative process.

For the vast majority of all organizations, innovation is a process that requires a workforce to gradually and progressively acquire the capabilities to adopt more sophisticated technologies.

The vast majority of all people and organizations want to buy a productivity improvement for existing operations. They are looking to minimize the disruption of their current methods. And they want evolution, not revolution.

The Adoption of Innovations Process

Diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system.

Everett Rogers, the pre-eminent authority on how innovations spread, defined innovation as:

“…an idea, practice, or object perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption.” (Rogers, 2003)

Rogers’ theory, developed in 1962, has become the standard guide and reference on diffusion studies.

It originated in communication to explain how, over time, an idea or product gains momentum and diffuses (or spreads) through a specific population or social system. The end result of this diffusion is that people, as part of a social system, adopt a new idea, behavior, or product.

Adoption means that a person does something differently than what they had previously (i.e., purchase or use a new product, acquire and perform a new behavior, etc.). And the key to adoption is that the person must perceive the idea, behavior, or product as new or innovative. It is through this that diffusion is possible.

Adoption of a new idea, behavior, or product does not happen simultaneously; rather it is a process whereby some people are more apt to adopt the innovation than others.

Researchers have found that people who adopt an innovation early have different characteristics than people who adopt an innovation later. And these characteristics are specific to the innovation being considered.

When promoting an innovation to a target population, it is important to understand the characteristics of the target population that will help or hinder adoption of the innovation.

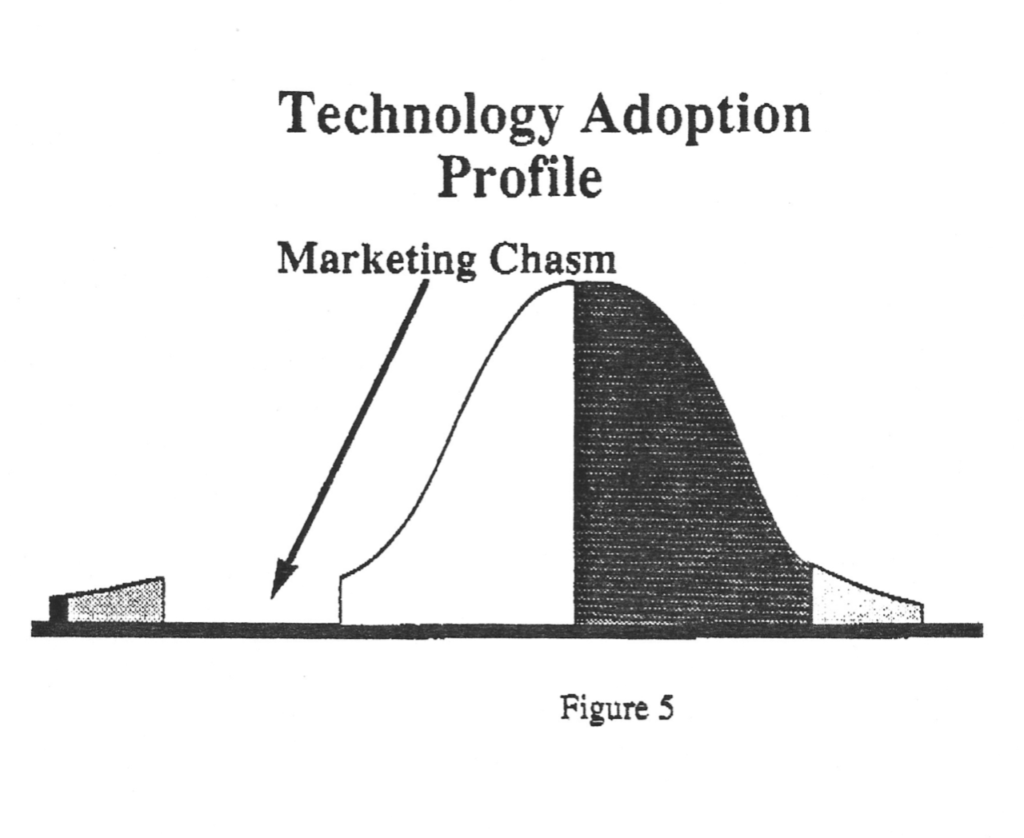

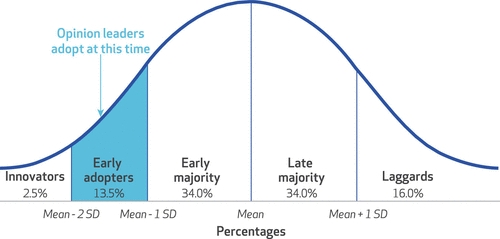

There are five established adopter categories, and while the majority of the general population tends to fall in the middle categories, it is still necessary to understand the characteristics of the of each adopter group because different strategies must be used to appeal to the different adopter categories.

Innovators – These are people who want to be the first to try the innovation. They are venturesome and interested in new things. These people are very willing to take risks, and are often the first to develop new innovations. Very little, if anything, needs to be done to appeal to this population.

Early Adopters – These are people who represent opinion leaders. They enjoy leadership roles, and embrace change opportunities. They are already aware of the need to change and so are very comfortable adopting new ideas. In general, they do not need to be persuaded or convinced to change.

Early Majority – These people are rarely leaders, but they do adopt new ideas before the average person. That said, they typically need to see evidence that the innovation works before they are willing to adopt it. Strategies to appeal to this population include success stories and evidence of the innovation’s effectiveness.

Late Majority – These people are skeptical of change, and will only adopt an innovation after it has been tried by the majority. Strategies to appeal to this population include information on how many other people have tried the innovation and have adopted it successfully.

Laggards – These people are bound by tradition and are very conservative. They are very skeptical of change and are the hardest group to bring on board. Strategies to appeal to this population include statistics, fear appeals, and pressure from people in the other adopter groups.

Key Drivers of the Adoption of Innovations

Diffusion of Innovations takes a very different approach to describing change than most other behavioral theories. Instead of focusing on persuading individuals to change, it describes change as being caused by the evolution or “reinvention” of products and services, so they become a better fit for the needs of individuals and groups. In Diffusion of Innovations, it is not people who change, but the innovations themselves.

Impersonal marketing methods like advertising and storytelling may spread information about new innovations, but it is conversations that spread adoption.

Why do certain innovations spread more quickly than others? And why do others fail? Rogers and his colleagues identified five qualities that determine the success of an innovation:

1) Relative advantage

Relative advantage is the extent to which an idea or product is perceived as better than the method in current practice. The greater the improvement — as measured by a particular group of users in terms that matter to those users — the greater the chance of adoption.

2) Compatibility

This is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with existing values and practices. An innovation that is compatible with the values, past experiences, and practices of potential adopters will be adopted rapidly.

3) Complexity

This is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand and use. New ideas that are simpler to understand are adopted more rapidly than innovations that require the adopter to develop new skills and behaviors.

4) Trialability

This is the degree to which an innovation can be experimented with on a limited basis. An innovation that is “trialable” represents less uncertainty and lower risk to the individual who is considering it.

5) Observability

The easier it is for individuals to see the results of an innovation, the more likely they are to adopt it. Visible results lower uncertainty and also stimulate peer discussion of a new idea, as friends and neighbors of an adopter often request information about it.

Summary

During the process of diffusion, an innovation is communicated through communication channels among the members of a social system. The innovation-decision process describes the stages an individual can go through while contemplating the adoption of an innovation. After having gained knowledge about it, the individual forms an opinion about the innovation and decides whether or not to adopt it.

The individual then starts using the innovation and further reduces the remaining uncertainty by practice and learning. When the innovation has been adopted, the individual continues to monitor whether adoption still makes sense for her.

Adopters as well as attributes of innovations can be divided into categories established by diffusion research. Their characteristics can provide an estimate of the probability of adoption in a given situation. Social networks have a large influence on the adoption process.