Worries about loss of progress or lost advantage, relying on an unproven vendor, and the absence of peer-level support hold many people back from adopting new products. This obstacle has been referred to as innovation disruption.

Introduction

This research study explores the ways an organization can create an innovation that accounts for the human need for safety.

Many people believe that breakthrough innovations are automatically accepted and widely adopted throughout society. But that assumption is flawed. Whereas the systems for enabling, formalizing and managing the innovation process seem to be improving, the fact remains that more than 90% of all new products and innovations fail, even if they provide obvious advantages.

The good news is the adoption of meaningful innovations and technologies can be systematically ensured using a framework that is based on the principles of neuroscience.

Without us knowing it, our amygdala – the “threat detector” and one of the oldest and more primitive parts of the brain – is constantly scanning our environment to assess our level of safety and alert us to any signs of trouble. It’s a basic survival mechanism with the goal of protecting us and keeping us safe. It was especially useful in prehistoric times when the threat of physical danger was omnipresent. But the amygdala can bypass the prefrontal cortex (the more newly-evolved part of our brain) and rapidly alert the body to danger.

Subconsciously, we see innovation as noxious and disruptive, and this bias can potentially discourage us from adopting a new product or trying an innovative new method. The reasons for this implicit bias against innovation can be traced to the fundamentally disruptive nature of novel and original creations. Innovation means change, without the certainty of desirable results.

We have an implicit belief the status quo is safe. And the people invested in the status quo have plenty of incentive not to change. For example, novel ideas have almost no upside for a middle manager. The goal of a middle manager is meeting metrics of an existing paradigm.

The key finding of this study is that risk (or lack of safety) is in the eyes of the beholder. What might be perceived as high risk to some people is seen as low risk to others. And the greatest ambiguity comes from our discovery that an individual’s perception of risk can vary widely from one innovation to another. In other words, a person can be the first on her block to buy an electric car, and at the same time the last to accept a COVID vaccination. Within the same person, EVs can be perceived as low risk and vaccinations can be perceived as high risk, and there is no method for predicting how someone will evaluate an innovation. The perception of risk is “innovation-specific.”

Perceived Risk Causes Innovation Disruption

Every new technology or innovation that is presented as a step forward carries a unique amount of perceived risk, which is determined by the organization or the end user. Some innovations are perceived as low risk by a majority of people, while others are seen as extremely risky by everyone except for a few high-stakes risk takers. This creates an environment of unpredictability for those developing anything new because each person will assign a different amount (or type) of risk to each new innovation they encounter.

The potential risks associated with adopting a new innovation can be long and varied. Our recent polling of mid-level managers identified the following risks as most prevalent:

- financial loss

- performance loss

- loss of respect (social loss)

- loss of time

- loss of privacy

Yet nine out of ten vendors are doing nothing to address these specific fears, which explains the 90% failure rate of new products. In essence, they are hoping that the promised value of their innovation will be enough to overcome the fear-based resistance that prevents adoption.

Given innovation’s critical importance to sustained growth, that is a risky strategy. Leading innovators and entrepreneurial organizations not only recognize the role that risk plays but also use a structured method of reducing the perceived risk of an innovation that involves the constant reinvention of the product.

To understand what a risk-reduction strategy entails, we analyzed the characteristics and attributes of over three dozen breakthrough innovations that have achieved full, mainstream adoption and identified the similarities in the elements that are directly related to reducing the perception of risk.

We found that the harmonious fit an innovation has with current methods, the innovator’s dedication to the end-user’s market, and the existence of independent systems of support, all correlate highly with the overall acceptance and success of the innovation.

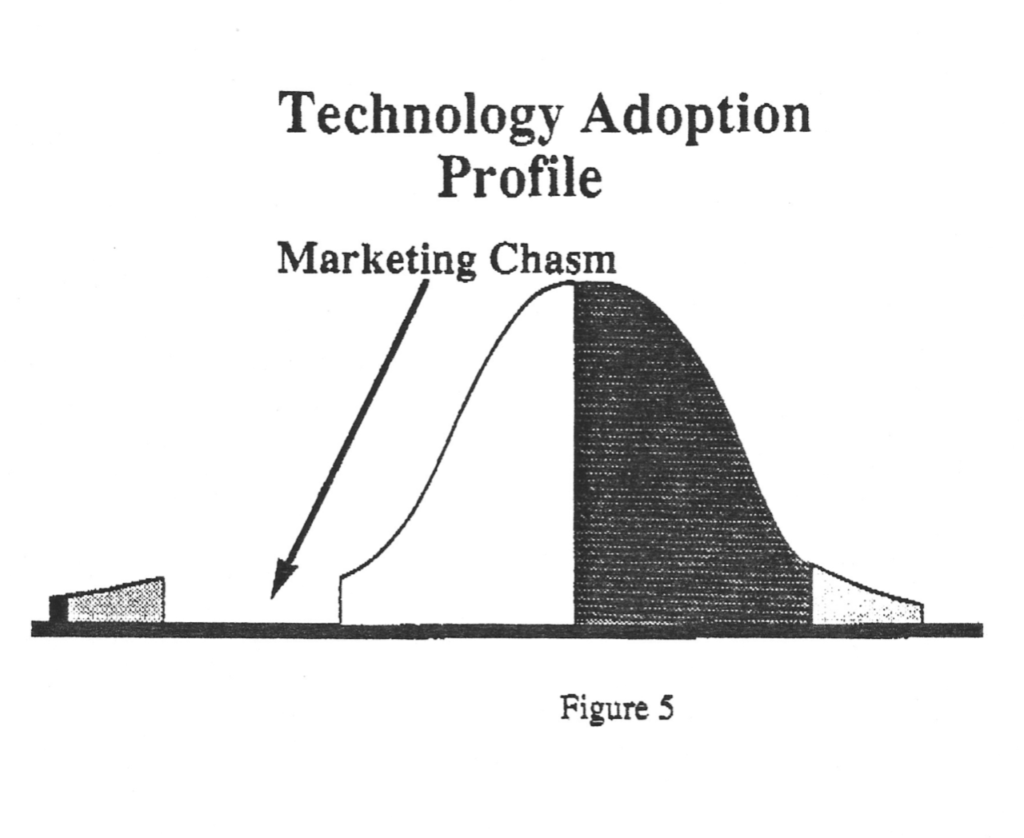

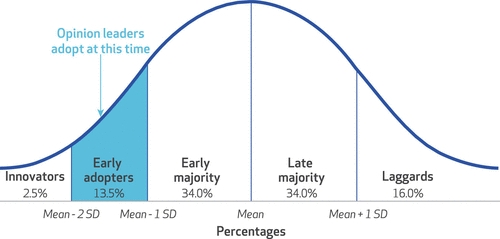

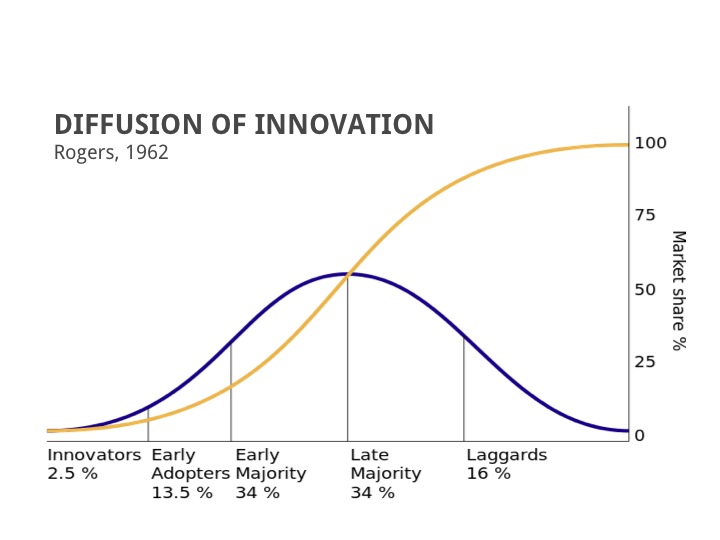

At the same time, the likelihood of innovation disruption increases as the innovation or product matures. Yet there are multiple methods that are proven to reduce the perception of risk and these methods can have an additive effect throughout the adoption lifecycle.

How do people measure risk?

Risk perception is a complex and personal topic — what prompts a person to adopt something new can motivate others to avoid it at all cost. In aggregate, however, our research shows that three types [categories] of risk prevent people from adopting an innovation in almost all cases: loss of prior progress or existing advantage, relying on an unproven vendor, and the absence of independent peer-level support. These risk factors act as barriers to innovation in every type of industry or market, where the innovation is classified as “discontinuous” — meaning it is expensive or complex, or it requires a change in workflow and/or new learning.

We were fascinated to discover when studying potential buyers of electric cars that loss of established-prior progress emerged as the biggest source of risk, being 4 times more prevalent than other sources. Such worries can have severe consequences. When we believe our decisions can put our current freedom of mobility at risk, loss aversion takes the steering wheel and drives us to stay with our current method. This results in buyers being reluctant to gamble their transportation habits on an innovation.

All successful mainstream innovations have attributes that alleviate these loss-based concerns by making the innovation fully compatible and familiar with existing methods and workflows. For example, Thomas Edison had an expert understanding of both innovation adoption and methods for overcoming the fear of loss. Recognizing that many commercial and residential landowners in New York had invested considerable capital in gas infrastructure to light their buildings, Edison chose to run his first electrical wires through existing gas lines, fitting directly into the system people had already invested in. And Edison’s strategy of adapting his technology to systems people already had in place, led to the accelerated acceptance and adoption of the electric lightbulb.

The second-biggest source of innovation disruption is the uncertainty surrounding the long-term viability of the vendor or supplier. Fear that is based in uncertainty and loss of control trigger the ambiguity effect, a cognitive bias that leads us to avoid options with uncertain outcomes. Buyers and end users seeking reassurance often look for signs of the vendor’s commitment to and investment in the market segment where the innovation is applied. Sponsorship by a trusted institution carries a significant amount of risk reduction and credibility. To allay their fear of uncertainty, some vendors focus on factors such as prestige, image and reputation—a risky approach, particularly in dynamic times.

This fear plagues mainstream buyers much more than it does early adopters. The vast majority of buyers don’t want to discover their supplier has gone out of business, and they are now stuck with products that no one will support. They look for compatible products that are fully tested, adhere to industry standards, and are used by others they know in their industry. Early adopters on the other hand are attracted by high-risk, high-reward projects.

The absence of peer-level support, the third persistent cause of innovation disruption, is a well-known and studied dynamic. Group conformity, social cohesion and tribalism are basic survival instincts, but these tendencies consistently prevent people from adopting new things. Social norms shape a person’s sense of what is possible, discouraging them from adopting new methods that break with convention. This conformity bias leads us to follow our peers, even if it means maintaining the status quo and missing opportunities for advancement.