The Diffusion Paradigm

Diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among members of a social system. The diffusion paradigm began with the 1943 publication of the results of a hybrid seed corn study conducted by Bryce Ryan and Neal C. Gross, rural sociologists at Iowa State University.

Diffusion of Innovations is a communication theory which has laid the groundwork for behavior change models across sciences and industries, representing a widely applicable perspective.The diffusion paradigm spread among midwestern rural sociological researchers in the 1950s and 1960s, and then to a larger, interdisciplinary field of diffusion scholars.

By the late 1960s, rural sociologists lost interest in diffusion studies, not because it was ineffective scientifically, but because of lack of support for such study as a consequence of farm overproduction and because most of the interesting research questions were thought to be answered.

Since 1943, more than 4000 research publications have appeared and diffusion research became a widely practiced variety of scholarly study in sociology and other social sciences. This paper describes some of the history of rural sociological research on the diffusion of agricultural innovations with the goal of understanding how the research tradition emerged and to determine how it influenced the larger body of diffusion research conducted later by scholars in other disciplinary specialties. The authors describe how diffusion of innovations research followed and deviated from the Kuhnian concept of paradigm development.

According to Rogers (1995), the study of the diffusion of innovations (DOI) can be traced back to the investigations of French sociologist Gabriel Tarde (p. 52). Tarde attempted to explain why some innovations are adopted and spread throughout a society, while others are ignored. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Tarde was witness to the development of many new inventions, many of which led to social and cultural change.

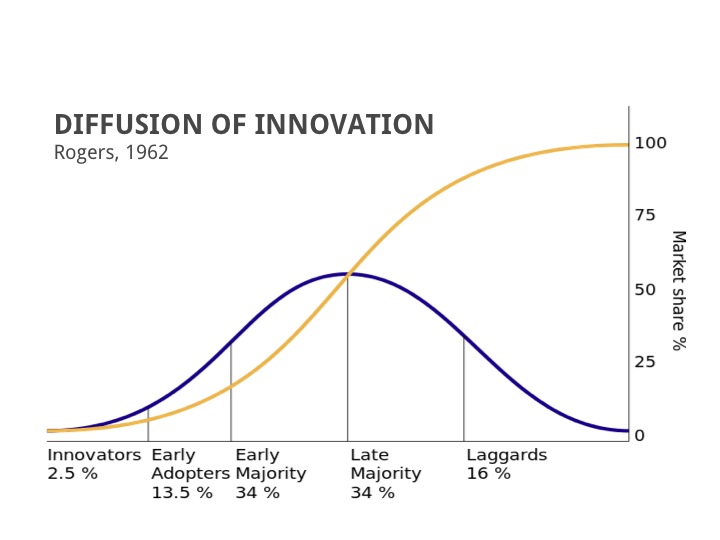

In his book The Laws of Imitation (1903), Tarde introduced the S-shaped curve and opinion leadership, focusing on the role of socioeconomic status (for example, a cosmopolitan individual is more likely to adopt new products). Even though he did not specify and clarify key diffusion concepts, his insights affected the development of many social scientific disciplines such as geography, economics, and anthropology. Sociologist F. Stuart Chapin, for example, studied longitudinal growth patterns in various social institutions, and found that S-shaped curves best described the adoption of phenomena such as the commission form of city government (Lowery & Defleur, 1995, p. 118).

Basic research of the diffusion paradigm

The fundamental research paradigm for the diffusion of innovations can be traced to the Iowa study of hybrid seed corn. Bryce Ryan and Neal C. Gross (1943) investigated the diffusion of hybrid seed corn among Iowa farmers. According to Lowery and DeFleur (1995), the background of rural sociology should first be understood before one can discuss how and why the hybrid seed corn study was conducted.

The Morrill Act helped “the states establish educational institutions that would be of special benefit to rural youth” (p. 120). Federal funds and other financial supports were given to these land-grant institutions in order to increase the development of the nation’s agricultural industry (p. 120). After World War II, rural sociologists changed their research focus on human problems among farmers because new agricultural technology such as new pesticides, new farm machine, and hybrid seed corn appeared. But in spite of these developments, some farmers ignored or resisted these new innovations.

Rural sociologists at land-grant universities in the Midwestern United States such as Iowa State, Michigan State, and Ohio State Universities, performed many diffusion studies to find out the causes of adoption of innovations. One of these efforts was the hybrid seed corn study conducted by Ryan and Gross (1943). These researchers attempted to explain why some farmers adopted the hybrid seed corn, while others did not.

Bryce Ryan and Neal C. Gross

Bryce Ryan earned a Ph. D in sociology at Harvard University. During his doctoral studies, Ryan was required to take interdisciplinary courses in economics, anthropology, and social psychology. This intellectual background helped him conduct the diffusion studies. In 1938, Ryan became a professor at Iowa State University which is known for its agricultural focus.

At that time, Iowa State administrators were worried about the slow rate at which the hybrid seed corn was being adopted. Despite the fact that the use of this new innovation could lead to an increase in quality and production, an advantageous adoption by Iowa Farmers was slow.

Ryan proposed the study of the diffusion of the hybrid seed corn and received funding from Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station, Iowa State University’s research and development organization. Contrary to previous research, which employed anthropological style approaches using qualitative methods, Ryan employed a quantitative survey method in his study. According to Rogers (1996), Ryan was encouraged to use this quantitative method by “professors in the Department of Statistics, such as Paul G. Homemeyer, Ray J. Jessen, and Snedecor” (p. 415).

When Ryan arrived at Iowa State University, Neal C. Gross was a graduate student who was soon assigned as Ryan’s research assistant. Ryan asked him to conduct interviews with Iowa farmers through survey research. Gross gathered the data from the Iowa communities of Jefferson and Grand Junction.

Rogers (1996) mentioned that “by coincidence, these communities were located within 30 miles of where he grew up on a farm” (p. 415). It is also interesting to note that Rogers earned a Ph. D. in sociology and statistics at Iowa State University in 1957.

The Iowa Study of Hybrid Corn Seed

As noted above, the hybrid seed corn had many advantages compared to traditional seed, such as the hybrid seed’s vigor and resistance to drought and disease. However, there were some barriers to prevent Iowa farmers from adopting the hybrid seed corn. One problem was that the hybrid seed corn could not reproduce (p. 122). This meant that the hybrid seed was relatively expensive for Iowa farmers, especially at the time of the Depression. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that, despite the economic profit that the hybrid seed corn provided, its high price kept adoption slow among Iowa farmers.

According to Lowery and DeFleur (1995), Ryan and Gross sought to explain how the hybrid seed corn came to attention and which of two channels (i.e., mass communication and interpersonal communication with peers) led farmers to adopt the new innovation. They found that each channel has different functions.

Mass communication functioned as the source of initial information, while interpersonal networks functioned as the influence over the farmers’ decisions to adopt (p. 125). One of the most important findings in this study is that “the adoption of innovation depends on some combination of well-established interpersonal ties and habitual exposure to mass communication” (p. 127).

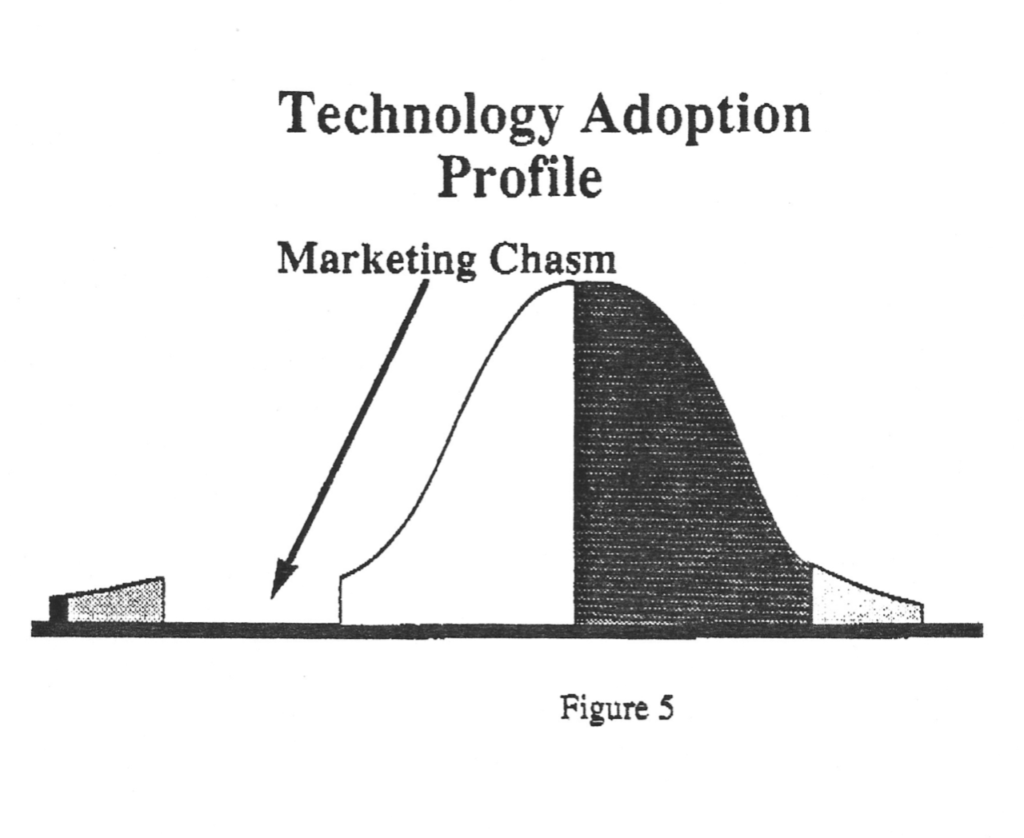

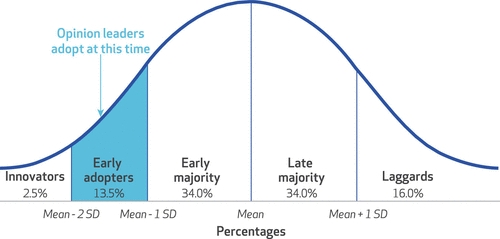

Ryan and Gross also found that the rate of adoption of hybrid seed corn followed an S-shaped curve, and that there were four different types of adopters.

According to Rogers (1995), Ryan and Gross also contributed by identifying the five major stages in the adoption process, which were awareness, interest, evaluation, trial, and adoption. After Ryan and Gross’s hybrid corn study, about 5,000 papers about diffusion were published in 1994 (Rogers, 1995).

The following psychographic profiles were abstracted from Rogers’ work while studying the diffusion of farm practices among farmers located in Iowa:

Innovators

They have larger than average farms, are well educated and usually come from well-established families. They usually have a relatively high net worth and, probably more important, a large amount of risk capital. They can afford and do take calculated risks on new products. They are respected for being successful, but ordinarily do not enjoy the highest prestige in the community. Because innovators adopt new ideas so much sooner than the average farmer, they are sometimes ridiculed by their conservative neighbors. This neighborhood group pressure is largely ignored by the innovators, however. The innovations are watched by their neighbors, but they are not followed immediately in new practices.

The activities of innovators often transcend local community boundaries. Rural innovators frequently belong to formal organizations at the county, regional, state, or national level. In addition, they are likely to have many informal contacts outside the community: they may visit with others many miles away who are also trying a new technique or product, or who are technical experts.

Early Adopters

They are younger than the average farmer, but not necessarily younger than the innovators. They also have a higher average education, and participate more in the formal activities of the community through such organizations as churches, the PTA, and farm organizations. They participate more than the average in agricultural cooperatives and in government agency programs in the community (such as Extension Service or Soil Conservation). In fact, there is some evidence that this group furnishes a disproportionate amount of the formal leadership (elected officers) in the community. Early adopters are also respected as good sources of new farm information by their neighbors.

Early Majority

The early majority are slightly above average in age, education, and farming experience. They have medium high social and economic status. They are less active in formal groups than innovators or early adopters, but more active than those who adopt later. In many cases, they are not formal leaders in the community organizations, but they are active members in these organizations. They also attend Extension meetings and farm demonstrations.

The people in this category are most likely to be informal rather than elected leaders. They have a following insofar as people respect their opinions, their “high morality and sound judgment.” They are “just like their following, only more so.” They must be sure an idea will work before they adopt it. If the informal leader fails two or three times, his following looks elsewhere for information and guidance. Because the informal leader has more limited resources than the early adopters and innovators, he cannot afford to make poor decisions: the social and economic costs are too high.

These people tend to associate mainly in their own community. When people in the community are asked to name neighbors and farmers with whom they talk over ideas, these early majority are named disproportionally frequently. On their parts, they value highly the opinions their neighbors and friends hold about them, for this is their main source of status and prestige. The early majority may look to the early adopters for their new farm information.

Late majority

Those in this group have less education and are older than the average farmer. While they participate less actively in formal groups, they probably form the bulk of the membership in these formal organizations. Individually they belong to fewer organizations, are less active in organizational work, and take fewer leadership roles than earlier adopters. They do not participate in as many activities outside the community as do people who adopt earlier.

Laggards

They have the least education and are the oldest. They participate least in formal organizations, cooperatives, and government agency programs. They have the smallest farms and the least capital. Many are suspicious of county extension agents and agricultural salesmen.