Introduction

The focus of this study was to gather information related to the development of chasm theory, and make it available for use within the concept formation framework. Our primary goal was to reduce confusion and help students gain a clearer understanding of the chasm framework and its applications.

Chasm Theory Project Description

This research project falls into the category of “Formal Research” meaning it is a style of research in which data is gathered in a very controlled, structured, systematic and objective way. Formal research requires the application of a structured approach as well as a common documentation methodology by the researchers.

Research Parameters

- This study draws on internal documents, case studies and training literature, as well as over 40 interviews with people familiar with the initial creation of the chasm concept — including consultants, co-workers, managers, academics, and clients — all of whom had direct contact with the concept creators and/or were clients of the Regis McKenna consulting practice.

- About half of the interviews were conducted from 2018 to 2019, with the remaining interviews conducted between 2020 and 2023.

- The interviews were semi-structured and explored the use of the chasm concept inside Regis Mckenna Inc., along with the experiences of clients who had purchased consulting services from the company.

Overview of Chasm Theory

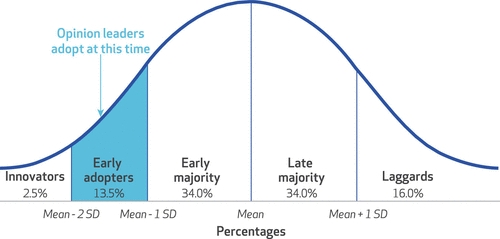

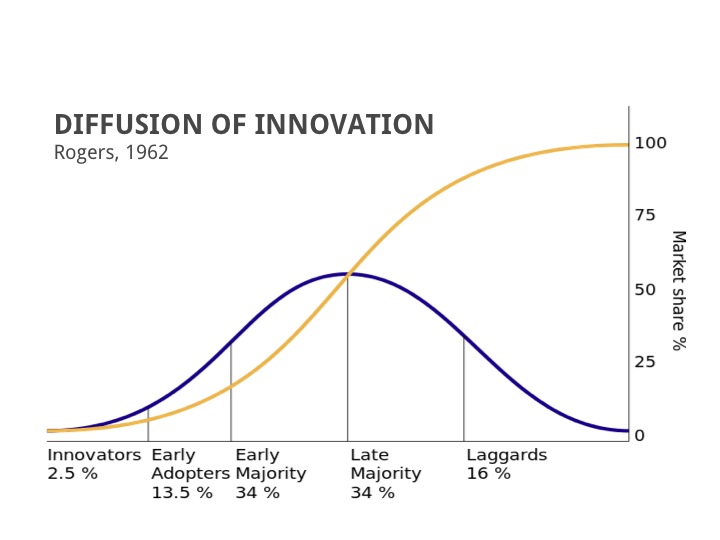

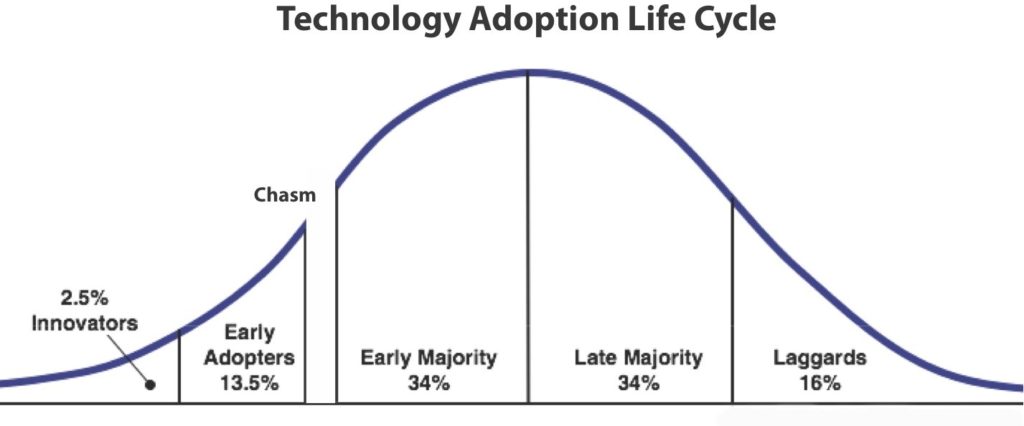

Chasm theory (also known as Crossing the Chasm) is an adaptation of a market development model called Diffusion of Innovations, that was developed by Everett Rogers in 1962. Similar to Diffusion of Innovations, chasm theory seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technologies are accepted by a group or population.

The underlying thesis of both Diffusion of Innovations and the chasm theory is that innovations are absorbed into any given user base in stages corresponding to psychological and social profiles of segments within that user community.

The process can be represented by a bell curve with definable stages; each associated with a definable group, and each group making up a predictable portion of the whole community.

The Origins of Chasm Theory Development

On July 23, 1915, Margaret McGrew was one of two children killed by an automobile in the State of Ohio.

At the time, the automobile was a new “discontinuous” innovation and less than 10% of all families owned cars, which means the primary form of transportation was based on horses.

After this tragic event, the McGrew family received unexpected reactions and statements made by members of the local community.

The strange and unusual comments a McGrew sibling received, specifically related to the new innovation called the automobile, fell into three distinct categories:

- a very small percentage of people (only a handful) said: your sister’s death is a terrible tragedy, and it is very unfortunate. But it is the price of progress.

- another small group of people said: we don’t think your sister’s death was really the fault of the automobile, we think it was YOUR fault.

- a very large percentage of people (over 85%) said: your sister’s death is proof that automobiles are not safe, and they must be outlawed forever…starting today!!

These highly divergent reactions by the public regarding the death of Margaret McGrew revealed the foundation of the chasm concept.

Despite the traumatic family-related circumstances, it provides valuable insight into how the public evaluates new products and innovations. And although it’s not practical as a research tool, it is easy to see the diametric opposition between the early supporters of an innovation, and the people in the mainstream. This opposition becomes crystal clear immediately after a tragedy that is caused by that new innovation.

The unfiltered reactions of the Youngstown Ohio community indicated that a small percentage of people support innovations despite tragic consequences. Yet people in the mainstream delay the acceptance of new innovations until the risk of both purchase and use is very low, and they wait for numerous systems to be established that ensure both low risk and safety.

This dramatic difference formed the theory, later proposed by Warren Schirtzinger and Lee James, called the marketing chasm.

Confirmed by Studies of Diffusion

The unexpected observations by Dan McGrew, were later explained by an expert in innovation-adoption at the Ohio State University in 1958.

Dan McGrew became a professor of dairy science at Ohio State and his new colleague — another relatively new professor named Everett Rogers — had been studying the way innovations spread by observing the patterns of adoption among farmers. This topic was also the focal-point of Professor McGrew’s career because, as an agricultural extension agent, it was his responsibility to encourage farmers to use new, innovative techniques of farming in order to increase agricultural production.

During a faculty meeting, Everett Rogers revealed the connection between the public reactions McGrew observed in 1915, and the psychographic profiles Rogers used in his model of innovation-diffusion. Professor Rogers explained the reasons behind the strange and unusual comments Dan McGrew received in Youngstown following the death of his sister:

- The people who said “this is the price of progress” are innovators, because they want new innovations to be adopted by everyone.

- The people who said “it was your fault” are early adopters, because they have a dream of changing the world, and they don’t want anything to interfere with their dream.

- The people who said “the automobile must be outlawed immediately” are members of the mainstream (early and late majority) because the mass market is primarily focused on avoiding risk and answering the question ‘what happens if something goes wrong?’

In a strategy conversation at Regis McKenna Inc.’s Northwest office in 1989, Lee James and Warren Schirtzinger were discussing the death of Warren’s aunt (Margaret McGrew). Mr. James compared the death of Margaret McGrew to the adoption of new laws by state governments. When Lee James created the “Right Turn on Red Law” while working at the Federal Energy Administration during the 1970s oil crisis, he noticed that an initial group of states including: California, Utah, Oregon, Arizona, Nevada, Washington, Alaska, and Colorado, adopted the new law quickly. But the remaining 42 states resisted adoption for an extended period of time.

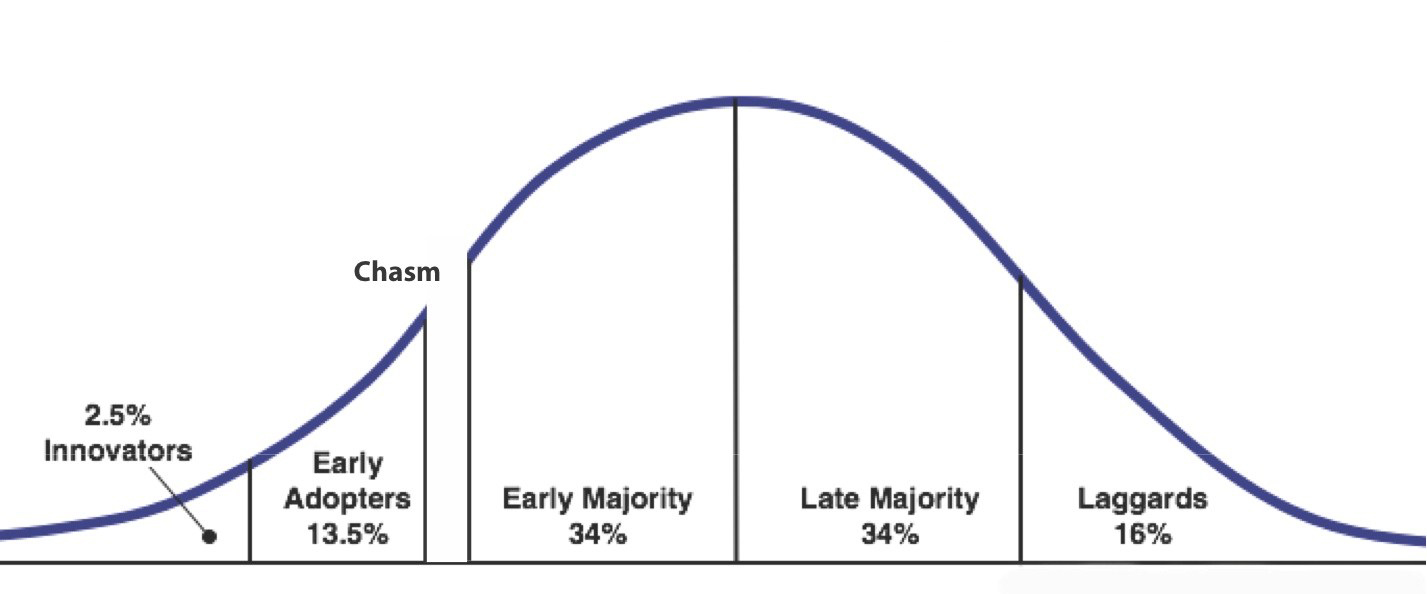

Together, James and Schirtzinger concluded that the reactions of the public in 1915 to a death caused by a discontinuous innovation, are a mirror image of the way prospective customers react to a new high-tech product: a small percentage are willing to accept the risks and a large percentage are not willing to accept the risk. And for discontinuous high-tech products, there is a gap in Rogers’ innovation-adoption curve. They decided to name it “the marketing chasm.”

Their chasm concept fundamentally stated that “innovators and early adopters have very different values and motivations than people in the mainstream.” And for the marketing consultants at Regis McKenna Inc., this means that many of the tactics that initially lead to success in an early market, will work against you in the mainstream market.

Chasm Theory Development Environment

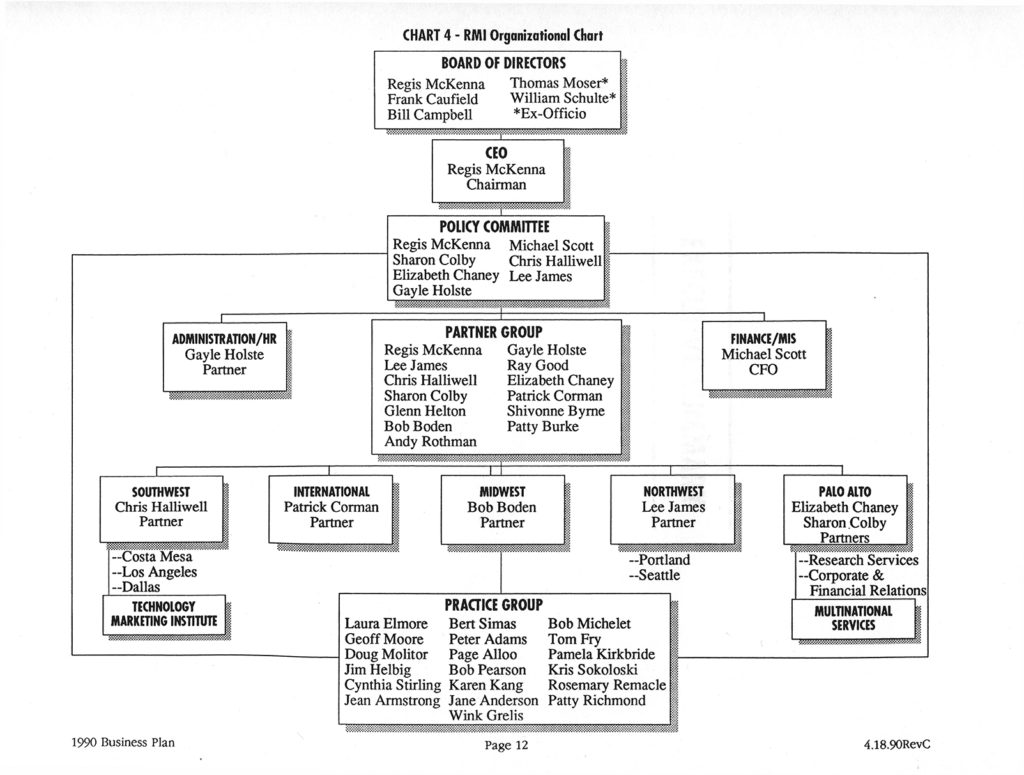

Founded in 1970, Regis McKenna Inc. (RMI) was a technology marketing consulting firm, which provided hands-on research, analysis, competitive strategies and implementation of marketing and communication programs.

By 1989, the firm had grown to $17 million in revenues, making it the largest technology-focused, marketing communications firm in the United States.

In 1987, RMI began repositioning the firm to offer higher value-added consulting services. Consulting clients in 1990 included: Apple, Hewlett-Packard, National Semiconductor, DuPont, Silicon Graphics, Ashton-Tate, Litton, Xerox, Digital Equipment, and Pacific Bell.

In 1985, Regis McKenna removed himself from day-to-day operations and operated as Chairman of the Board leaving the firm in the hands of a newly-recruited management team. In 1986, McKenna joined the venture capital firm of Kleiner, Perkins Caufield and Byers as a general partner. However, in the time frame of 12 months the President/CEO, CFO, and COO were asked to leave due to continuing poor financial performance.

Regis McKenna re-assumed the role of CEO and day-to-day management of RMI in January, 1989. While he remained a general partner of KPC&B IV, that fund had been completely invested or committed. He was identified as a Venture Partner of KPC&B, but had none of the responsibilities for the KPCB Partnership management.

RMI Situation and Objectives

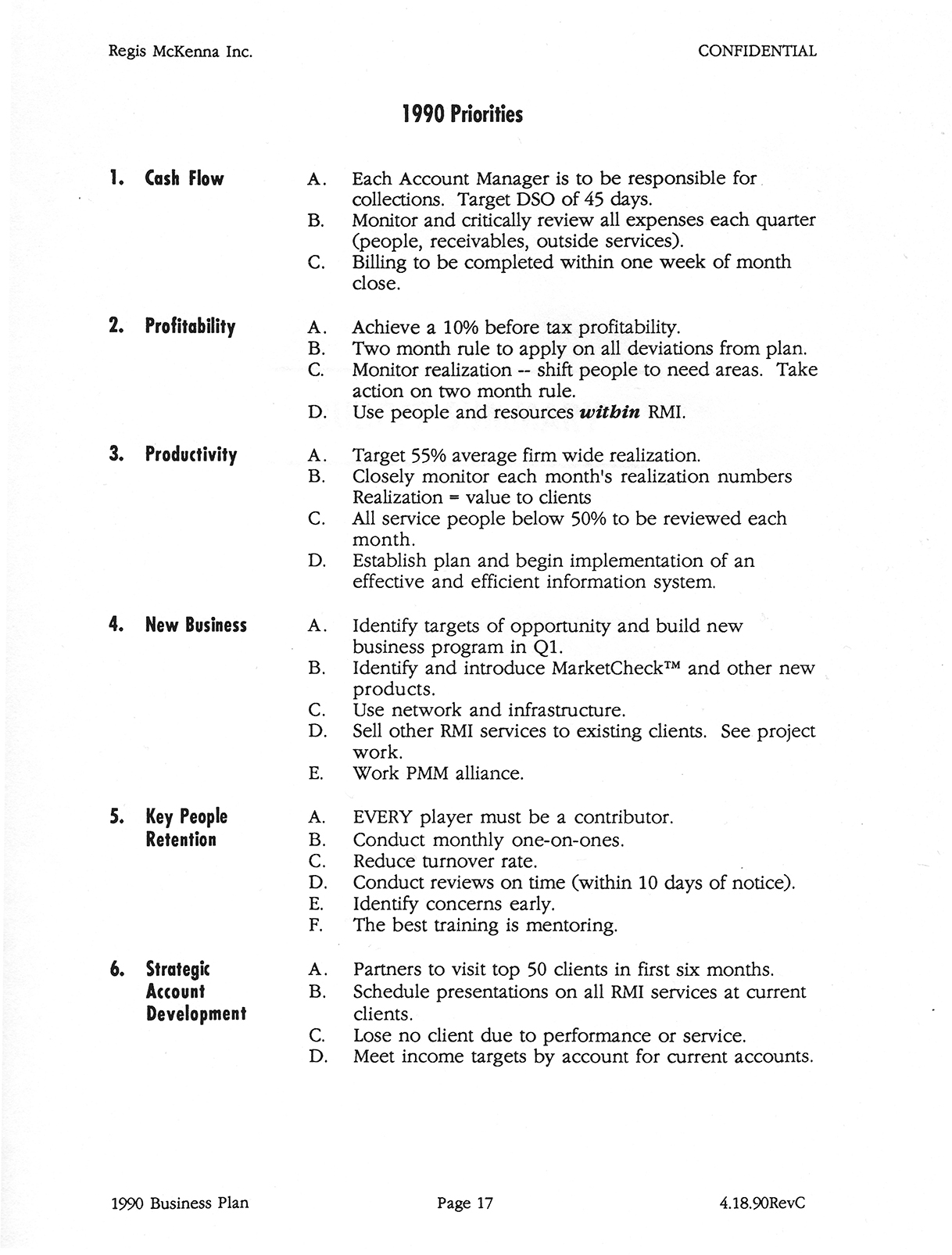

RMI’s goal was to become the “High Tech McKinsey” of marketing. As the largest high-technology consulting firm in the United States, the company’s plan was to grow its business to $20 million by 1993 with 10% to 15% growth per year. Management’s top priority was to put RMI on a sound track to growth and profit.

Those familiar with RMI would often state that certain characteristics of the firm’s consultants could easily prevent the achievement of positive financial results. And even though employees were characterized as very bright people who were also very creative, they were also known to be aggressive, impatient and arrogant with a “know it all” mentality.

In 1989, RMI focused their energies on cash management, expense control, new business development and acquiring new people. They put into place a strategic account plan that was intended to focus their human resources on key clients and prospects. (see notes to 1990 financial plan)

RMI’s intent was to grow their business with fully staffed offices in Palo Alto, Los Angeles, and Portland. Support offices located in Seattle, Dallas, and Minneapolis would have minimum staffs.

In 1989, over one-third of the clients served by RMI-Northwest were clients outside the region. And over 60% of the revenue was from clients not served in 1988, indicating substantial client turnover. In 1990, the intent was to place a greater focus on the Northwest Region.

RMI’s London office had been acquired by KPMG and was being operated as “Regis McKenna LTD” within the KPMG structure. This entity represented RMI clients and business opportunities in Europe. In 1989, RMI formally established an international business group operating from Palo Alto with consulting services offered primarily throughout the Pacific Basin.

Management reduced the number organizational levels from nine to four and identified 14 senior people as “Partners.” Two areas of cash and profit drain, the RMI offices in Paris and Boston, were closed in the first quarter of 1990.

After Regis McKenna stepped aside at the end of 1989, RMI was managed by its Partner Group.

In addition to financial difficulties, the owner of the firm (Mr. Regis McKenna) had become aware of the general lack of inter-office collaboration throughout RMI and decided that all RMI offices needed to begin sharing the results of their consulting projects throughout the company.

McKenna called this initiative “merchandising RMI.” It was designed to encourage all consultants to share the success of projects with other offices.

Diffusion of Innovations, Updated for High Tech

Everett Rogers’ research and subsequent development of Diffusion of Innovations was based on studying farmers and their willingness to adopt a new type of hybrid corn seed.

In 1989, a group of senior consultants and partners at Regis McKenna Inc. formed a task force with the mission of updating the psychographic descriptions of defined adopter groups in the diffusion model. The goal was to take the original descriptions of farmers that were created by Everett Rogers, and translate those characteristics into descriptions of high-tech buyers. The task force developed new descriptions of each adopter type, renamed each group, and also renamed the diffusion framework.

Innovators

Early Adopters

Early Majority

Late Majority

Laggards

—>

—>

—>

—>

—>

technology enthusiasts

visionaries

pragmatists

followers (then conservatives)

resisters (then skeptics)

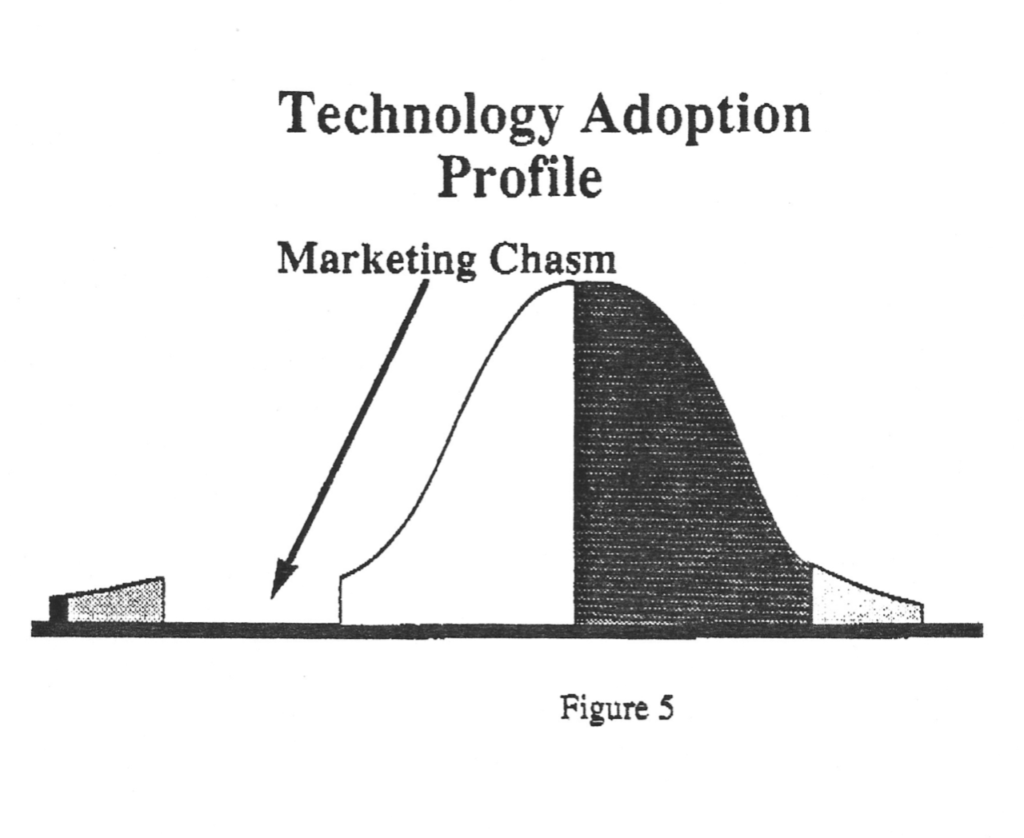

After renaming the adopter groups, the Diffusion of Innovations framework was re-named the “Technology Adoption Lifecycle.”

This project to re-define the Diffusion model provided an opportunity for an author working at Regis McKenna Inc. to write and publish a new book. The new book would theoretically replace Diffusion of Innovations as the go-to guide for commercializing high-tech products. That author was G. Moore, and he began writing that book about the newly-created Technology Adoption Lifecycle. His book was called: High Tech Marketing – Changes in the Game. [see PaineWebber document below]

Internal documents from Regis McKenna Inc., obtained by Diffusion Research Institute, indicate that the definitions and descriptions of the Technology Adoption Lifecycle were being used in client engagements prior to the publishing of the new book that was being crafted.

The chasm theory itself was originally developed and first used as a market strategy in the same year the RMI task force was updating Diffusion of Innovations to the Technology Adoption Lifecycle.

In mid-1989, RMI consultants Lee James and Warren Schirtzinger were discussing the death of Warren’s aunt that was caused by a brand new, novel innovation.

They concluded that novel innovations, many of which are high-tech products, are often rejected by a mainstream audience, and even fail, even though they are initially well received.

While many of the partners and senior consultants at RMI were discussing and re-defining Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations model, James and Schirtzinger were identifying and describing a gap in the innovation-adoption curve.

That gap is located between early adopters and the mainstream early majority where large groups of customers are realistic and practical rather than adventurous.

Together they decided to label this phenomenon “the marketing chasm,” and the new framework was used extensively by James, Schirtzinger and others in the Pacific Northwest.

An example of chasm theory being used in a client engagement in the Pacific Northwest in 1989 is shown here:

NeuroCom Engagement

<– use of chasm theory in 1989, shown on page 5

A review of internal RMI documents from Silicon Valley and other locations indicate that no one outside of the Pacific Northwest was using the chasm theory in client engagements until 1991.

The client deliverables displayed below, including documents prepared for Samsung and Paine Webber in 1990, show no indication of chasm theory in terms of content, knowledge or understanding. The Technology Adoption Lifecycle is used extensively, but nothing about chasm theory was included.

PaineWebber Engagement

<– Chasm theory is missing in this product marketing workshop, delivered in 1990. This document also states the adoption curve is a continuum, confirming the lack of chasm theory knowledge. (page 1, paragraph 2)

<– no mention of a chasm between early adopters and the early majority.

<– footnote indicates a new book is being written by Geoffrey Moore in 1990 about the technology adoption lifecycle called High Tech Marketing, Changes in the Game.

Samsung Engagement

<– This document from RMI in Palo Alto was delivered as part of a Samsung Engagement in 1990. It shows no knowledge of chasm theory

<– no mention of a chasm between early adopters and the early majority.

Teradata Engagement

<– This document from RMI in Palo Alto was delivered in 1990. It shows no knowledge, understanding or use of chasm theory.

<– no mention of a chasm between early adopters and the early majority.

Controversy, Resentment and Company Demise

Multiple interviewees highlighted the resentment that was caused inside Regis McKenna Inc. by the publication of the book called “Crossing the Chasm.”

Several former partners reported that intellectual property developed at RMI – including the chasm concept, the whole product concept, the positioning/messaging template, day-in-the-life analysis, and the positioning compass – were all taken and included in the book without discussion or permission.

The end result of this infringement by Geoff Moore was widespread resentment, loss of revenue, and ultimately the firm’s demise. In approximately one year following publication of the book, all revenue-producing partners had left the firm.

Conclusion

A thorough review of relevant documents from Regis McKenna Inc., along with interviews with people close to the firm (employees, clients, partners and allies) confirm that the chasm concept was developed by Lee James and Warren Schirtzinger in the year 1989.

The concept was initially proposed by Warren Schirtzinger based on his experience related to the death of his great aunt, who was killed in 1915 by a new innovation called the automobile. Lee James then compared that event to his observation that essentially all high-tech markets react to new innovations in a similar way.

After initially resisting the idea of a gap in the adoption curve, mostly due to financial concerns, the chasm concept became a cornerstone framework for all consultants at Regis McKenna, Inc. And the book project called “High Tech Marketing; Changes in the Game” was restructured and became Crossing the Chasm which was published late in 1991.

Research Philosophy

The goal of all research projects at Diffusion Research Institute is to ensure the accuracy of our studies in three ways: observable verification, consistency of findings, and actionable utility.

This means we verify facts using a significant number of observations. We look for consistency between a statement and an accepted body of knowledge. And we test to see if a claim or proposition is successfully actionable.